Understanding ASP.NET View State

Introduction

Microsoft® ASP.NET view state, in a nutshell, is the technique used by an ASP.NET Web page to persist changes to the state of a Web Form across postbacks. In my experiences as a trainer and consultant, view state has caused the most confusion among ASP.NET developers. When creating custom server controls or doing more advanced page techniques, not having a solid grasp of what view state is and how it works can come back to bite you. Web designers who are focused on creating low-bandwidth, streamlined pages oftentimes find themselves frustrated with view state, as well. The view state of a page is, by default, placed in a hidden form field named __VIEWSTATE. This hidden form field can easily get very large, on the order of tens of kilobytes. Not only does the __VIEWSTATE form field cause slower downloads, but, whenever the user posts back the Web page, the contents of this hidden form field must be posted back in the HTTP request, thereby lengthening the request time, as well.

This article aims to be an in-depth examination of the ASP.NET view state. We’ll look at exactly what view state is storing, and how the view state is serialized to the hidden form field and deserialized back on postback. We’ll also discuss techniques for reducing the bandwidth required by the view state.

Note This article is geared toward the ASP.NET page developer rather than the ASP.NET server control developer. This article therefore does not include a discussion on how a control developer would implement saving state. For an in-depth discussion on that issue, refer to the book Developing Microsoft ASP.NET Server Controls and Components.

Before we can dive into our examination of view state, it is important that we first take a quick moment to discuss the ASP.NET page life cycle. That is, what exactly happens when a request comes in from a browser for an ASP.NET Web page? We’ll step through this process in the next section.

The ASP.NET Page Life Cycle

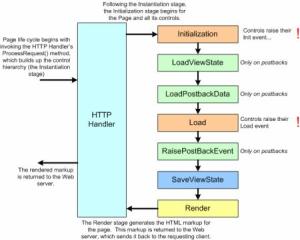

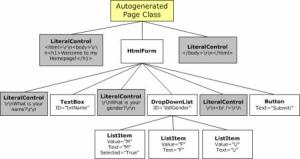

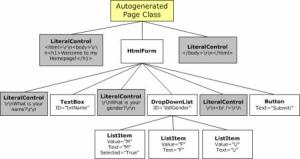

Each time a request arrives at a Web server for an ASP.NET Web page, the first thing the Web server does is hand off the request to the ASP.NET engine. The ASP.NET engine then takes the request through a pipeline composed of numerous stages, which includes verifying file access rights for the ASP.NET Web page, resurrecting the user’s session state, and so on. At the end of the pipeline, a class corresponding to the requested ASP.NET Web page is instantiated and the ProcessRequest() method is invoked (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. ASP.NET Page Handling

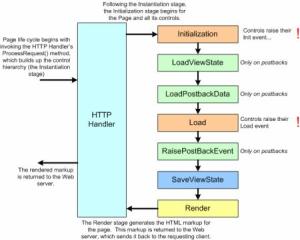

This life cycle of the ASP.NET page starts with a call to the ProcessRequest() method. This method begins by initializing the page’s control hierarchy. Next, the page and its server controls proceed lock-step through various phases that are essential to executing an ASP.NET Web page. These steps include managing view state, handling postback events, and rendering the page’s HTML markup. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the ASP.NET page life cycle. The life cycle ends by handing off the Web page’s HTML markup to the Web server, which sends it back to the client that requested the page.

Note A detailed discussion of the steps leading up to the ASP.NET page life cycle is beyond the scope of this article. For more information read Michele Leroux-Bustamante’s Inside IIS & ASP.NET. For a more detailed look at HTTP handlers, which are the endpoints of the ASP.NET pipeline, check out my previous article on HTTP Handlers.

What is important to realize is that each and every time an ASP.NET Web page is requested it goes through these same life cycle stages (shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Events in the Page Life Cycle

Stage 0 – Instantiation

The life cycle of the ASP.NET page begins with instantiation of the class that represents the requested ASP.NET Web page, but how is this class created? Where is it stored?

ASP.NET Web pages, as you know, are made up of both an HTML portion and a code portion, with the HTML portion containing HTML markup and Web control syntax. The ASP.NET engine converts the HTML portion from its free-form text representation into a series of programmatically-created Web controls.

When an ASP.NET Web page is visited for the first time after a change has been made to the HTML markup or Web control syntax in the .aspx page, the ASP.NET engine auto-generates a class. If you created your ASP.NET Web page using the code-behind technique, this autogenerated class is derived from the page’s associated code-behind class (note that the code-behind class must be derived itself, either directly or indirectly, from the System.Web.UI.Page class); if you created your page with an in-line, server-side <script> block, the class derives directly from System.Web.UI.Page. In either case, this autogenerated class, along with a compiled instance of the class, is stored in the WINDOWS\Microsoft.NET\Framework\version\Temporary ASP.NET Files folder, in part so that it doesn’t need to be recreated for each page request.

The purpose of this autogenerated class is to programmatically create the page’s control hierarchy. That is, the class is responsible for programmatically creating the Web controls specified in the page’s HTML portion. This is done by translating the Web control syntax—<asp:WebControlName Prop1=”Value1″ … />—into the class’s programming language (C# or Microsoft® Visual Basic® .NET, most typically). In addition to the Web control syntax being converted into the appropriate code, the HTML markup present in the ASP.NET Web page’s HTML portion is translated to Literal controls.

All ASP.NET server controls can have a parent control, along with a variable number of child controls. The System.Web.UI.Page class is derived from the base control class (System.Web.UI.Control), and therefore also can have a set of child controls. The top-level controls declared in an ASP.NET Web page’s HTML portion are the direct children of the autogenerated Page class. Web controls can also be nested inside one another. For example, most ASP.NET Web pages contain a single server-side Web Form, with multiple Web controls inside the Web Form. The Web Form is an HTML control (System.Web.UI.HtmlControls.HtmlForm). Those Web controls inside the Web Form are children of the Web Form.

Since server controls can have children, and each of their children may have children, and so on, a control and its descendents form a tree of controls. This tree of controls is called the control hierarchy. The root of the control hierarchy for an ASP.NET Web page is the Page-derived class that is autogenerated by the ASP.NET engine.

Whew! Those last few paragraphs may have been a bit confusing, as this is not the easiest subject to discuss or digest. To clear out any potential confusion, let’s look at a quick example. Imagine you have an ASP.NET Web page with the following HTML portion:

<html>

<body>

<h1>Welcome to my Homepage!</h1>

<form runat=”server”>

What is your name?

<asp:TextBox runat=”server” ID=”txtName”></asp:TextBox>

<br />What is your gender?

<asp:DropDownList runat=”server” ID=”ddlGender”>

<asp:ListItem Select=”True” Value=”M”>Male</asp:ListItem>

<asp:ListItem Value=”F”>Female</asp:ListItem>

<asp:ListItem Value=”U”>Undecided</asp:ListItem>

</asp:DropDownList>

<br />

<asp:Button runat=”server” Text=”Submit!”></asp:Button>

</form>

</body>

</html>

When this page is first visited, a class will be autogenerated that contains code to programmatically build up the control hierarchy. The control hierarchy for this example can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Control Hierarchy for sample page

This control hierarchy is then converted to code that is similar to the following:

Page.Controls.Add(

new LiteralControl(@”<html>\r\n<body>\r\n

<h1>Welcome to my Homepage!</h1>\r\n”));

HtmlForm Form1 = new HtmlForm();

Form1.ID = “Form1”;

Form1.Method = “post”;

Form1.Controls.Add(

new LiteralControl(“\r\nWhat is your name?\r\n”));

TextBox TextBox1 = new TextBox();

TextBox1.ID = “txtName”;

Form1.Controls.Add(TextBox1);

Form1.Controls.Add(

new LiteralControl(“\r\n<br />What is your gender?\r\n”));

DropDownList DropDownList1 = new DropDownList();

DropDownList1.ID = “ddlGender”;

ListItem ListItem1 = new ListItem();

ListItem1.Selected = true;

ListItem1.Value = “M”;

ListItem1.Text = “Male”;

DropDownList1.Items.Add(ListItem1);

ListItem ListItem2 = new ListItem();

ListItem2.Value = “F”;

ListItem2.Text = “Female”;

DropDownList1.Items.Add(ListItem2);

ListItem ListItem3 = new ListItem();

ListItem3.Value = “U”;

ListItem3.Text = “Undecided”;

DropDownList1.Items.Add(ListItem3);

Form1.Controls.Add(

new LiteralControl(“\r\n<br /> \r\n”));

Button Button1 = new Button();

Button1.Text = “Submit!”;

Form1.Controls.Add(Button1);

Form1.Controls.Add(

new LiteralControl(“\r\n</body>\r\n</html>”));

Controls.Add(Form1);

Note The C# source code above is not the precise code that is autogenerated by the ASP.NET engine. Rather, it’s a cleaner and easier to read version of the autogenerated code. To see the full autogenerated code—which won’t win any points for readability—navigate to the WINDOWS\Microsoft.NET\Framework\Version\Temporary ASP.NET Files folder and open one of the .cs or .vb files.

One thing to notice is that, when the control hierarchy is constructed, the properties that are explicitly set in the declarative syntax of the Web control are assigned in the code. (For example, the Button Web control has its Text property set to “Submit!” in the declarative syntax – Text=”Submit!” – as well as in the autogenerated class—Button1.Text = “Submit!”;.

Stage 1 – Initialization

After the control hierarchy has been built, the Page, along with all of the controls in its control hierarchy, enter the initialization stage. This stage is marked by having the Page and controls fire their Init events. At this point in the page life cycle, the control hierarchy has been constructed, and the Web control properties that are specified in the declarative syntax have been assigned.

We’ll look at the initialization stage in more detail later in this article. With regards to view state it is important for two reasons; first, server controls don’t begin tracking view state changes until right at the end of the initialization stage. Second, when adding dynamic controls that need to utilize view state, these controls will need to be added during the Page’s Init event as opposed to the Load event, as we’ll see shortly.

Stage 2 – Load View State

The load view state stage only happens when the page has been posted back. During this stage, the view state data that had been saved from the previous page visit is loaded and recursively populated into the control hierarchy of the Page. It is during this stage that the view state is validated. As we’ll discuss later in this article, the view state can become invalid due to a number of reasons, such as view state tampering, and injecting dynamic controls into the middle of the control hierarchy.

Stage 3 – Load Postback Data

The load postback data stage also only happens when the page has been posted back. A server control can indicate that it is interested in examining the posted back data by implementing the IPostBackDataHandler interface. In this stage in the page life cycle, the Page class enumerates the posted back form fields, and searches for the corresponding server control. If it finds the control, it checks to see if the control implements the IPostBackDataHandler interface. If it does, it hands off the appropriate postback data to the server control by calling the control’s LoadPostData() method. The server control would then update its state based on this postback data.

To help clarify things, let’s look at a simple example. One nice thing about ASP.NET is that the Web controls in a Web Form remember their values across postback. That is, if you have a TextBox Web control on a page and the user enters some value into the TextBox and posts back the page, the TextBox’s Text property is automatically updated to the user’s entered value. This happens because the TextBox Web control implements the IPostBackDataHandler interface, and the Page class hands off the appropriate value to the TextBox class, which then updates its Text property.

To concretize things, imagine that we have an ASP.NET Web page with a TextBox whose ID property is set to txtName. When the page is first visited, the following HTML will be rendered for the TextBox: <input type=”text” id=”txtName” name=”txtName” />. When the user enters a value into this TextBox (such as, “Hello, World!”) and submits the form, the browser will make a request to the same ASP.NET Web page, passing the form field values back in the HTTP POST headers. These include the hidden form field values (such as __VIEWSTATE), along with the value from the txtName TextBox.

When the ASP.NET Web page is posted back in the load postback data stage, the Page class sees that one of the posted back form fields corresponds to the IPostBackDataHandler interface. There is such a control in the hierarchy, so the TextBox’s LoadPostData() method is invoked, passing in the value the user entered into the TextBox (“Hello, World!”). The TextBox’s LoadPostData() method simply assigns this passed in value to its Text property.

Notice that in our discussion on the load postback data stage, there was no mention of view state. You might naturally be wondering, therefore, why I bothered to mention the load postback data stage in an article about view state. The reason is to note the absence of view state in this stage. It is a common misconception among developers that view state is somehow responsible for having TextBoxes, CheckBoxes, DropDownLists, and other Web controls remember their values across postback. This is not the case, as the values are identified via posted back form field values, and assigned in the LoadPostData() method for those controls that implement IPostBackDataHandler.

Stage 4 – Load

This is the stage with which all ASP.NET developers are familiar, as we’ve all created an event handler for a page’s Load event (Page_Load). When the Load event fires, the view state has been loaded (from stage 2, Load View State), along with the postback data (from stage 3, Load Postback Data). If the page has been posted back, when the Load event fires we know that the page has been restored to its state from the previous page visit.

Stage 5 – Raise Postback Event

Certain server controls raise events with respect to changes that occurred between postbacks. For example, the DropDownList Web control has a SelectedIndexChanged event, which fires if the DropDownList’s SelectedIndex has changed from the SelectedIndex value in the previous page load. Another example: if the Web Form was posted back due to a Button Web control being clicked, the Button’s Click event is fired during this stage.

There are two flavors of postback events. The first is a changed event. This event fires when some piece of data is changed between postbacks. An example is the DropDownLists SelectedIndexChanged event, or the TextBox’s TextChanged event. Server controls that provide changed events must implement the IPostBackDataHandler interface. The other flavor of postback events is the raised event. These are events that are raised by the server control for whatever reason the control sees fit. For example, the Button Web control raises the Click event when it is clicked, and the Calendar control raises the VisibleMonthChanged event when the user moves to another month. Controls that fire raised events must implement the IPostBackEventHandler interface.

Since this stage inspects postback data to determine if any events need to be raised, the stage only occurs when the page has been posted back. As with the load postback data stage, the raise postback event stage does not use view state information at all. Whether or not an event is raised depends on the data posted back in the form fields.

Stage 6 – Save View State

In the save view state stage, the Page class constructs the page’s view state, which represents the state that must persist across postbacks. The page accomplishes this by recursively calling the SaveViewState() method of the controls in its control hierarchy. This combined, saved state is then serialized into a base-64 encoded string. In stage 7, when the page’s Web Form is rendered, the view state is persisted in the page as a hidden form field.

Stage 7 – Render

In the render stage the HTML that is emitted to the client requesting the page is generated. The Page class accomplishes this by recursively invoking the RenderControl() method of each of the controls in its hierarchy.

These seven stages are the most important stages with respect to understanding view state. (Note that I did omit a couple of stages, such as the PreRender and Unload stages.) As you continue through the article, keep in mind that every single time an ASP.NET Web page is requested, it proceeds through these series of stages.

The Role of View State

View state’s purpose in life is simple: it’s there to persist state across postbacks. (For an ASP.NET Web page, its state is the property values of the controls that make up its control hierarchy.) This begs the question, “What sort of state needs to be persisted?” To answer that question, let’s start by looking at what state doesn’t need to be persisted across postbacks. Recall that in the instantiation stage of the page life cycle, the control hierarchy is created and those properties that are specified in the declarative syntax are assigned. Since these declarative properties are automatically reassigned on each postback when the control hierarchy is constructed, there’s no need to store these property values in the view state.

For example, imagine we have a Label Web control in the HTML portion with the following declarative syntax:

<asp:Label runat=”server” Font-Name=”Verdana”

Text=”Hello, World!”></asp:Label>

When the control hierarchy is built in the instantiation stage, the Label’s Text property will be set to “Hello, World!” and its Font property will have its Name property set to Verdana. Since these properties will be set each and every page visit during the instantiation stage, there’s no need to persist this information in the view state.

What needs to be stored in the view state is any programmatic changes to the page’s state. For example, suppose that in addition to this Label Web control, the page also contained two Button Web controls, a Change Message Button and an Empty Postback button. The Change Message Button has a Click event handler that assigns the Label’s Text property to “Goodbye, Everyone!”; the Empty Postback Button just causes a postback, but doesn’t execute any code. The change to the Label’s Text property in the Change Message Button would need to be saved in the view state. To see how and when this change would be made, let’s walk through a quick example. Assuming that the HTML portion of the page contains the following markup:

<asp:Label runat=”server” ID=”lblMessage”

Font-Name=”Verdana” Text=”Hello, World!”></asp:Label>

<br />

<asp:Button runat=”server”

Text=”Change Message” ID=”btnSubmit”></asp:Button>

<br />

<asp:Button runat=”server” Text=”Empty Postback”></asp:Button>

And the code-behind class contains the following event handler for the Button’s Click event:

private void btnSubmit_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

lblMessage.Text = “Goodbye, Everyone!”;

}

Figure 4 illustrates the sequence of events that transpire, highlighting why the change to the Label’s Text property needs to be stored in the view state.

Figure 4. Events and View State

To understand why saving the Label’s changed Text property in the view state is vital, consider what would happen if this information were not persisted in view state. That is, imagine that in step 2’s save view state stage, no view state information was persisted. If this were the case, then in step 3 the Label’s Text property would be assigned to “Hello, World!” in the instantiation stage, but would not be reassigned to “Goodbye, Everyone!” in the load view state stage. Therefore, from the end user’s perspective, the Label’s Text property would be “Goodbye, Everyone!” in step 2, but would seemingly be reset to its original value (“Hello, World!”) in step 3, after clicking the Empty Postback button.

View State and Dynamically Added Controls

Since all ASP.NET server controls contain a collection of child controls exposed through the Controls property, controls can be dynamically added to the control hierarchy by appending new controls to a server control’s Controls collection. A thorough discussion of dynamic controls is a bit beyond the scope of this article, so we won’t cover that topic in detail here; instead, we’ll focus on how to manage view state for controls that are added dynamically. (For a more detailed lesson on using dynamic controls, check out Dynamic Controls in ASP.NET and Working with Dynamically Created Controls.)

Recall that in the page life cycle, the control hierarchy is created and the declarative properties are set in the instantiation stage. Later, in the load view state stage, the state that had been altered in the prior page visit is restored. Thinking a bit about this, three things become clear when working with dynamic controls:

- Since the view state only persists changed control state across postbacks, and not the actual controls themselves, dynamically added controls must be added to the ASP.NET Web page, on both the initial visit as well as all subsequent postbacks.

- Dynamic controls are added to the control hierarchy in the code-behind class, and therefore are added at some point after the instantiation stage.

- The view state for these dynamically added controls is automatically saved in the save view state stage. (What happens on postback if the dynamic controls have not yet been added by the time the load view state stage rolls, however?)

So, dynamically added controls must be programmatically added to the Web page on each and every page visit. The best time to add these controls is during the initialization stage of the page life cycle, which occurs before the load view state stage. That is, we want to have the control hierarchy complete before the load view state stage arrives. For this reason, it is best to create an event handler for the Page class’s Init event in your code-behind class, and add your dynamic controls there.

Note You may be able to get away with loading your controls in the Page_Load event handler and maintaining the view state properly. It all depends on whether or not you are setting any properties of the dynamically loaded controls programmatically and, if so, when you’re doing it relative to the Controls.Add(dynamicControl) line. A thorough discussion of this is a bit beyond the scope of this article, but the reason it may work is because the Controls property’s Add() method recursively loads the parent’s view state into its children, even though the load view state stage has passed.

When adding a dynamic control c to some parent control p based on some condition (that is, when not loading them on each and every page visit), you need to make sure that you add c to the end of p‘s Controls collection. The reason is because the view state for p contains the view state for p‘s children as well, and, as we’ll discuss in the “Parsing the View State” section, p‘s view state specifies the view state for its children by index. (Figure 5 illustrates how inserting a dynamic control somewhere other than the end of the Controls collection can cause a corrupted view state.)

Figure 5. Effect of inserting controls on View State

The ViewState Property

Each control is responsible for storing its own state, which is accomplished by adding its changed state to its ViewState property. The ViewState property is defined in the System.Web.UI.Control class, meaning that all ASP.NET server controls have this property available. (When talking about view state in general I’ll use lower case letters with a space between view and state; when discussing the ViewState property, I’ll use the correct casing and code-formatted text.)

If you examine the simple properties of any ASP.NET server control you’ll see that the properties read and write directly to the view state. (You can view the decompiled source code for a .NET assembly by using a tool like Reflector.) For example, consider the HyperLink Web control’s NavigateUrl property. The code for this property looks like so:

public string NavigateUrl

{

get

{

string text = (string) ViewState[“NavigateUrl”];

if (text != null)

return text;

else

return string.Empty;

}

set

{

ViewState[“NavigateUrl”] = value;

}

}

As this code sample illustrates, whenever a control’s property is read, the control’s ViewState is consulted. If there is not an entry in the ViewState, then the default value for the property is returned. When the property is assigned, the assigned value is written directly to the ViewState.

Note All Web controls use the above pattern for simple properties. Simple properties are those that are scalar values, like strings, integers, Booleans, and so on. Complex properties, such as the Label’s Font property, which might be classes themselves, use a different approach. Consult the book Developing Microsoft ASP.NET Server Controls and Components for more information on state maintenance techniques for ASP.NET server controls.

The ViewState property is of type System.Web.UI.StateBag. The StateBag class provides a means to store name and value pairs, using a System.Collections.Specialized.HybridDictionary behind the scenes. As the NavigateUrl property syntax illustrates, items can be added to and queried from the StateBag using the same syntax you could use to access items from a Hashtable.

Timing the Tracking of View State

Recall that earlier I said the view state only stores state that needs to be persisted across postbacks. One bit of state that does not need to be persisted across postbacks is the control’s properties specified in the declarative syntax, since they are automatically reinstated in the page’s instantiation stage. For example, if we have a HyperLink Web control on an ASP.NET Web page and declaratively set the NavigateUrl property to http://www.scottonwriting.net/ then this information doesn’t need to be stored in the view state.

Seeing the HyperLink control’s NavigateUrl property’s code, however, it looks as if the control’s ViewState is written to whenever the property value is set. In the instantiation stage, therefore, where we’d have something like HyperLink1.NavigateUrl = http://www.ScottOnWriting.NET;, it would only make sense that this information would be stored in the view state.

Regardless of what might seem apparent, this is not the case. The reason is because the StateBag class only tracks changes to its members after its TrackViewState() method has been invoked. That is, if you have a StateBag, any and all additions or modifications that are made before TrackViewState() is made will not be saved when the SaveViewState() method is invoked. The TrackViewState() method is called at the end of the initialization stage, which happens after the instantiation stage. Therefore, the initial property assignments in the instantiation stage—while written to the ViewState in the properties’ set accessors—are not persisted during the SaveViewState() method call in the save view state stage, because the TrackViewState() method has yet to be invoked.

Note The reason the StateBag has the TrackViewState() method is to keep the view state as trimmed down as possible. Again, we don’t want to store the initial property values in the view state, as they don’t need to be persisted across postbacks. Therefore, the TrackViewState() method allows the state management to begin after the instantiation and initialization stages.

Storing Information in the Page’s ViewState Property

Since the Page class is derived from the System.Web.UI.Control class, it too has a ViewState property. In fact, you can use this property to persist page-specific and user-specific information across postbacks. From an ASP.NET Web page’s code-behind class, the syntax to use is simply:

ViewState[keyName] = value

There are a number of scenarios when being able to store information in the Page’s ViewState is useful. The canonical example is in creating a pageable, sortable DataGrid (or a sortable, editable DataGrid), since the sort expression must be persisted across postbacks. That is, if the DataGrid’s data is first sorted, and then paged, when binding the next page of data to the DataGrid it is important that you get the next page of the data when it is sorted by the user’s specified sort expression. The sort expression therefore needs to be persisted in some manner. There are assorted techniques, but the simplest, in my opinion, is to store the sort expression in the Page’s ViewState.

For more information on creating sortable, pageable DataGrids (or a pageable, sortable, editable DataGrid), pick up a copy of my book ASP.NET Data Web Controls Kick Start.

The Cost of View State

Nothing comes for free, and view state is no exception. The ASP.NET view state imposes two performance hits whenever an ASP.NET Web page is requested:

- On all page visits, during the save view state stage the Page class gathers the collective view state for all of the controls in its control hierarchy and serializes the state to a base-64 encoded string. (This is the string that is emitted in the hidden __VIEWSTATE form filed.) Similarly, on postbacks, the load view state stage needs to deserialize the persisted view state data, and update the pertinent controls in the control hierarchy.

- The __VIEWSTATE hidden form field adds extra size to the Web page that the client must download. For some view state-heavy pages, this can be tens of kilobytes of data, which can require several extra seconds (or minutes!) for modem users to download. Also, when posting back, the __VIEWSTATE form field must be sent back to the Web server in the HTTP POST headers, thereby increasing the postback request time.

If you are designing a Web site that is commonly accessed by users coming over a modem connection, you should be particularly concerned with the bloat the view state might add to a page. Fortunately, there are a number of techniques that can be employed to reduce view state size. We’ll first see how to selectively indicate whether or not a server control should save its view state. If a control’s state does not need to be persisted across postbacks, we can turn off view state tracking for that control, thereby saving the extra bytes that would otherwise have been added by that control. Following that, we’ll examine how to remove the view state from the page’s hidden form fields altogether, storing the view state instead on the Web server’s file system.

Disabling the View State

In the save view state stage of the ASP.NET page life cycle, the Page class recursively iterates through the controls in its control hierarchy, invoking each control’s SaveViewState() method. This collective state is what is persisted to the hidden __VIEWSTATE form field. By default, all controls in the control hierarchy will record their view state when their SaveViewState() method is invoked. As a page developer, however, you can specify that a control should not save its view state or the view state of its children controls by setting the control’s EnableViewState property to False (the default is True).

The EnableViewState property is defined in the System.Web.UI.Control class, so all server controls have this property, including the Page class. You can therefore indicate that an entire page’s view state need not be saved by setting the Page class’s EnableViewState to False. (This can be done either in the code-behind class with Page.EnableViewState = false; or as a @Page-level directive—<%@Page EnableViewState=”False” %>.)

Not all Web controls record the same amount of information in their view state. The Label Web control, for example, records only programmatic changes to its properties, which won’t greatly impact the size of the view state. The DataGrid, however, stores all of its contents in the view state. For a DataGrid with many columns and rows, the view state size can quickly add up! For example, the DataGrid shown in Figure 6 (and included in this article’s code download as HeavyDataGrid.aspx) has a view state size of roughly 2.8 kilobytes, and a total page size of 5,791 bytes. (Almost half of the page’s size is due to the __VIEWSTATE hidden form field!) Figure 7 shows a screenshot of the view state, which can be seen by visiting the ASP.NET Web page, doing a View\Source, and then locating the __VIEWSTATE hidden form field.

Figure 6. DataGrid control

Figure 7. View State for DataGrid control

The download for this article also includes an ASP.NET Web page called LightDataGrid.aspx, which has the same DataGrid as shown in Figure 6, but with the EnableViewState property set to False. The total view state size for this page? 96 bytes. The entire page size clocks in a 3,014 bytes. LightDataGrid.aspx boasts a view state size about 1/30th the size of HeavyDataGrid.aspx, and a total download size that’s about half of HeavyDataGrid.aspx. With wider DataGrids with more rows, this difference would be even more pronounced. (For more information on performance comparisons between view state-enabled DataGrids and view state-disabled DataGrids, refer to Deciding When to Use the DataGrid, DataList, or Repeater.)

Hopefully the last paragraph convinces you of the benefit of intelligently setting the EnableViewState property to False, especially for “heavy” view state controls like the DataGrid. The question now, is, “When can I safely set the EnableViewState property to False?” To answer that question, consider when you need to use the view state—only when you need to remember state across postbacks. The DataGrid stores its contents in the view state so the page developer doesn’t need to rebind the database data to the DataGrid on each and every page load, but only on the first one. The benefit is that the database doesn’t need to be accessed as often. If, however, you set a DataGrid’s EnableViewState property to False, you’ll need to rebind the database data to the DataGrid on both the first page load and every subsequent postback.

For a Web page that has a read-only DataGrid, like the one in Figure 6, you’d definitely want to set the DataGrid’s EnableViewState property to False. You can even create sortable and pageable DataGrids with the view state disabled (as can be witnessed in the LightDataGrid-WithFeatures.aspx page, included in the download), but, again, you’ll need to be certain to bind the database data to the DataGrid on the first page visit, as well as on all subsequent postbacks.

Note Creating an editable DataGrid with disabled view state requires some intricate programming, which involves parsing of the posted back form fields in the editable DataGrid. Such strenuous effort is required because, with an editable DataGrid blindly rebinding, the database data to the DataGrid will overwrite any changes the user made (see this FAQ for more information).

Specifying Where to Persist the View State

After the page has collected the view state information for all of the controls in its control hierarchy in the save view state stage, it persists it to the __VIEWSTATE hidden form field. This hidden form field can, of course, greatly add to the overall size of the Web page. The view state is serialized to the hidden form field in the Page class’s SavePageStateToPersistenceMedium() method during the save view state stage, and is deserialized by the Page class’s LoadPageStateFromPersistenceMedium() method in the load view state stage. With just a bit of work we can have the view state persisted to the Web server’s file system, rather than as a hidden form field weighing down the page. To accomplish this we’ll need to create a class that derives from the Page class and overrides the SavePageStateToPersistenceMedium() and LoadPageStateFromPersistenceMedium() methods.

Note There is a third-party product called Flesk.ViewStateOptimizer that reduces the view state bloat using a similar technique.

The view state is serialized and deserialized by the System.Web.UI.LosFormatter class—the LOS stands for limited object serialization—and is designed to efficiently serialize certain types of objects into a base-64 encoded string. The LosFormatter can serialize any type of object that can be serialized by the BinaryFormatter class, but is built to efficiently serialize objects of the following types:

- Strings

- Integers

- Booleans

- Arrays

- ArrayLists

- Hashtables

- Pairs

- Triplets

Note The Pair and Triplet are two classes found in the System.Web.UI namespace, and provide a single class to store either two or three objects. The Pair class has properties First and Second to access its two elements, while Triplet has First, Second, and Third as properties.

The SavePageStateToPersistenceMedium() method is called from the Page class and passed in the combined view state of the page’s control hierarchy. When overriding this method, we need to use the LosFormatter() to serialize the view state to a base-64 encoded string, and then store this string in a file on the Web server’s file system. There are two main challenges with this approach:

- Coming up with an acceptable file naming scheme. Since the view state for a page will likely vary based on the user’s interactions with the page, the stored view state must be unique for each user and for each page.

- Removing the view state files from the file system when they are no longer needed.

To tackle the first challenge, we’ll name the persisted view state file based on the user’s SessionID and the page’s URL. This approach will work beautifully for all users whose browsers accept session-level cookies. Those who do not accept cookies, however, will have a unique session ID generated for them on each page visit, thereby making this naming technique unworkable for them. For this article I’m just going to demonstrate using the SessionID / URL file name scheme, although it won’t work for those whose browsers are configured not to accept cookies. Also, it won’t work for a Web farm unless all servers store the view state files to a centralized location.

Note One workaround would be to use a globally unique identifier (GUID) as the file name for the persisted view state, saving this GUID in a hidden form field on the ASP.NET Web page. This approach, unfortunately, would take quite a bit more effort than using the SessionID / URL scheme, since it involves injecting a hidden form field into the Web Form. For that reason, I’ll stick to illustrating the simpler approach for this article.

The second challenge arises because, each time a user visits a different page, a new file holding that page’s view state will be created. Over time this will lead to thousands of files. Some sort of automated task would be needed to periodically clean out the view state files older than a certain date. I leave this as an exercise for the reader.

To persist view state information to a file, we start by creating a class that derives from the Page class. This derived class, then, needs to override the SavePageStateToPersistenceMedium() and LoadPageStateFromPersistenceMedium() methods. The following code presents such a class:

public class PersistViewStateToFileSystem : Page

{

protected override void

SavePageStateToPersistenceMedium(object viewState)

{

// serialize the view state into a base-64 encoded string

LosFormatter los = new LosFormatter();

StringWriter writer = new StringWriter();

los.Serialize(writer, viewState);

// save the string to disk

StreamWriter sw = File.CreateText(ViewStateFilePath);

sw.Write(writer.ToString());

sw.Close();

}

protected override object LoadPageStateFromPersistenceMedium()

{

// determine the file to access

if (!File.Exists(ViewStateFilePath))

return null;

else

{

// open the file

StreamReader sr = File.OpenText(ViewStateFilePath);

string viewStateString = sr.ReadToEnd();

sr.Close();

// deserialize the string

LosFormatter los = new LosFormatter();

return los.Deserialize(viewStateString);

}

}

public string ViewStateFilePath

{

get

{

string folderName =

Path.Combine(Request.PhysicalApplicationPath,

“PersistedViewState”);

string fileName = Session.SessionID + “-” +

Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(Request.Path).Replace(“/”,

“-“) + “.vs”;

return Path.Combine(folderName, fileName);

}

}

}

The class contains a public property ViewStateFilePath, which returns the physical path to the file where the particular view state information will be stored. This file path is dependent upon the user’s SessionID and the URL of the requested page.

Notice that the SavePageStateToPersistenceMedium() method accepts an object input parameter. This object is the view state object that is built up from the save view state stage. The job of SavePageStateToPersistenceMedium() is to serialize this object and persist it in some manner. The method’s code simply creates an instance of the LosFormatter object and invokes its Serialize() method, serializing the passed-in view state information to the StringWriter writer. Following that, the specified file is created (or overwritten, if it already exists) with the contents of the base-64 encoded, serialized view state string.

The LoadPageStateFromPersistenceMedium() method is called at the beginning of the load view state stage. Its job is to retrieve the persisted view state and deserialize back into an object that can be propagated into the page’s control hierarchy. This is accomplished by opening the same file where the persisted view state was stored on the last visit, and returning the deserialized version via the Deserialize() method in LosFormatter().

Again, this approach won’t work with users that do not accept cookies, but for those that do, the view state is persisted entirely on the Web server’s file system, thereby adding 0 bytes to the overall page size!

Note Another approach to reducing the bloat imposed by view state is to compress the serialized view state stream in the SavePageStateToPersistenceMedium() method, and then decompress it back to its original form in the LoadPageStateFromPersistenceMedium() method. Scott Galloway has a blog entry where he discusses his experiences with using #ziplib library to compress the view state.

Parsing the View State

When a page is rendered, it serializes its view state into a base-64 encoded string using the LosFormatter class and (by default) stores it in a hidden form field. On postback, the hidden form field is retrieved and deserialized back into the view state’s object representation, which is then used to restore the state of the controls in the control hierarchy. One detail we have overlooked up to this point in the article is what, exactly, is the structure of the Page class’s view state object?

As we discussed earlier, entire view state of the Page is the sum of the view state of the controls in its control hierarchy. Put another way, at any point in the control hierarchy, the view state of that control represents the view state of that control along with the view state of all of its children controls. Since the Page class forms the root of the control hierarchy, its view state represents the view state for the entire control hierarchy.

The Page class contains a SavePageViewState(), which is invoked during the page life cycle’s save view state stage. The SavePageViewState() method starts by creating a Triplet that contains the following three items:

- The page’s hash code. This hash code is used to ensure that the view state hasn’t been tampered with between postbacks. We’ll talk more about view state hashing in the “View State and Security Implications” section.

- The collective view state of the Page’s control hierarchy.

- An ArrayList of controls in the control hierarchy that need to be explicitly invoked by the page class during the raise postback event stage of the life cycle.

The First and Third items in the Triplet are relatively straightforward; the Second item is where the view state for the Page’s control hierarchy is maintained. The Second item is generated by the Page by calling the SaveViewStateRecursive() method, which is defined in the System.Web.UI.Control class. SaveViewStateRecursive() saves the view state of the control and its descendents by returning a Triplet with the following information:

- The state present in the Control’s ViewState StageBag.

- An ArrayList of integers. This ArrayList maintains the indexes of the Control’s child controls that have a non-null view state.

- An ArrayList of the view states for the children controls. The ith view state in this ArrayList maps to the child control index in the ith item in the ArrayList in the Triplet’s Second item.

The Control class computes the view state, returning a Triplet. The Second item of the Triplet contains the view state of the Control’s descendents. The end result is that the view state is comprised of many ArrayLists inside of Triplets inside of Triplets, inside of Triplets, inside of… (The precise contents in the view state depend on the controls in the hierarchy. More complex controls might serialize their own state to the view state using Pairs or object arrays. As we’ll see shortly, though, the view state is composed of a number of Triplets and ArrayLists nested as deep as the control hierarchy.)

Programmatically Stepping Through the View State

With just a little bit of work we can create a class that can parse through the view state and display its contents. The download for this article includes a class called ViewStateParser that provides such functionality. This class contains a ParseViewState() method that recursively steps through the view state. It takes in three inputs:

- The current view state object.

- How many levels deep we are in the view state recursion.

- A text label to display.

The last two input parameters are just for display purposes. The code of this method, shown below, determines the type of the current view state object and displays the contents of the view state accordingly, by recursively calling itself on each of the current object’s members. (The variable tw is a TextWriter instance to which the output is being written.)

protected virtual void ParseViewStateGraph(

object node, int depth, string label)

{

tw.Write(System.Environment.NewLine);

if (node == null)

{

tw.Write(String.Concat(Indent(depth), label, “NODE IS NULL”));

}

else if (node is Triplet)

{

tw.Write(String.Concat(Indent(depth), label, “TRIPLET”));

ParseViewStateGraph(

((Triplet) node).First, depth+1, “First: “);

ParseViewStateGraph(

((Triplet) node).Second, depth+1, “Second: “);

ParseViewStateGraph(

((Triplet) node).Third, depth+1, “Third: “);

}

else if (node is Pair)

{

tw.Write(String.Concat(Indent(depth), label, “PAIR”));

ParseViewStateGraph(((Pair) node).First, depth+1, “First: “);

ParseViewStateGraph(((Pair) node).Second, depth+1, “Second: “);

}

else if (node is ArrayList)

{

tw.Write(String.Concat(Indent(depth), label, “ARRAYLIST”));

// display array values

for (int i = 0; i < ((ArrayList) node).Count; i++)

ParseViewStateGraph(

((ArrayList) node)[i], depth+1, String.Format(“({0}) “, i));

}

else if (node.GetType().IsArray)

{

tw.Write(String.Concat(Indent(depth), label, “ARRAY “));

tw.Write(String.Concat(“(“, node.GetType().ToString(), “)”));

IEnumerator e = ((Array) node).GetEnumerator();

int count = 0;

while (e.MoveNext())

ParseViewStateGraph(

e.Current, depth+1, String.Format(“({0}) “, count++));

}

else if (node.GetType().IsPrimitive || node is string)

{

tw.Write(String.Concat(Indent(depth), label));

tw.Write(node.ToString() + ” (” +

node.GetType().ToString() + “)”);

}

else

{

tw.Write(String.Concat(Indent(depth), label, “OTHER – “));

tw.Write(node.GetType().ToString());

}

}

As the code shows, the ParseViewState() method iterates through the expected types—Triplet, Pair, ArrayList, arrays, and primitive types. For scalar values—integers, strings, etc.—the type and value are displayed; for aggregate types—arrays, Pairs, Triplets, etc.—the members that compose the type are displayed by recursively invoking ParseViewState().

The ViewStateParser class can be utilized from an ASP.NET Web page (see the ParseViewState.aspx demo), or can be accessed directly from the SavePageStateToPersistenceMedium() method in a class that is derived from the Page class (see the ShowViewState class). Figures 8 and9 show the ParseViewState.aspx demo in action. As Figure 8 shows, the user is presented with a multi-line textbox into which they can paste the hidden __VIEWSTATE form field from some Web page. Figure 9 shows a snippet of the parsed view state for a page displaying file system information in a DataGrid.

Figure 8. Decoding ViewState

Figure 9. ViewState decoded

In addition to the view state parser provided in this article’s download, Paul Wilson provides a view state parser on his Web site. Fritz Onion also has a view state decoder WinForms application available for download from the Resources section on his Web site.

View State and Security Implications

The view state for an ASP.NET Web page is stored, by default, as a base-64 encoded string. As we saw in the previous section, this string can easily be decoded and parsed, displaying the contents of the view state for all to see. This raises two security-related concerns:

- Since the view state can be parsed, what’s to stop someone from changing the values, re-serializing it, and using the modified view state?

- Since the view state can be parsed, does that mean I can’t place any sensitive information in the view state (such as passwords, connection strings, etc.)?

Fortunately, the LosFormatter class has capabilities to address both of these concerns, as we’ll see over the next two sections. Before we delve into the solutions for these concerns, it is important to first note that view state should only be used to store non-sensitive data. View state does not house code, and should definitely not be used to place sensitive information like connection strings or passwords.

Protecting the View State from Modification

Even though view state should only store the state of the Web controls on the page and other non-sensitive data, nefarious users could cause you headaches if they could successfully modify the view state for a page. For example, imagine that you ran an eCommerce Web site that used a DataGrid to display a list of products for sale along with their cost. Unless you set the DataGrid’s EnableViewState property to False, the DataGrid’s contents—the names and prices of your merchandise—will be persisted in the view state.

Nefarious users could parse the view state, modify the prices so they all read $0.01, and then deserialize the view state back to a base-64 encoded string. They could then send out e-mail messages or post links that, when clicked, submitted a form that sent the user to your product listing page, passing along the altered view state in the HTTP POST headers. Your page would read the view state and display the DataGrid data based on this view state. The end result? You’d have a lot of customers thinking they were going to be able to buy your products for only a penny!

A simple means to protect against this sort of tampering is to use a machine authentication check, or MAC. Machine authentication checks are designed to ensure that the data received by a computer is the same data that it transmitted out—namely, that it hasn’t been tampered with. This is precisely what we want to do with the view state. With ASP.NET view state, the LosFormatter performs a MAC by hashing the view state data being serialized, and appending this hash to the end of the view state. (A hash is a quickly computed digest that is commonly used in symmetric security scenarios to ensure message integrity.) When the Web page is posted back, the LosFormatter checks to ensure that the appended hash matches up with the hashed value of the deserialized view state. If it does not match up, the view state has been changed en route.

By default, the LosFormatter class applies the MAC. You can, however, customize whether or not the MAC occurs by setting the Page class’s EnableViewStateMac property. The default, True, indicates that the MAC should take place; a value of False indicates that it should not. You can further customize the MAC by specifying what hashing algorithm should be employed. In the machine.config file, search for the <machineKey> element’s validation attribute. The default hashing algorithm used is SHA1, but you can change it to MD5 if you like.

Note When using Server.Transfer() you may find you receive a problem with view state authentication. A number of articles online have mentioned that the only workaround is to set EnableViewStateMac to False. While this will certainly solve the problem, it opens up a security hole.

Encrypting the View State

Ideally the view state should not need to be encrypted, as it should never contain sensitive information. If needed, however, the LosFormatter does provide limited encryption support. The LosFormatter only allows for a single type of encryption: Triple DES. To indicate that the view state should be encrypted, set the <machineKey> element’s validation attribute in the machine.config file to 3DES.

In addition to the validation attribute, the <machineKey> element contains validationKey and decryptionKey attributes, as well. The validationKey attribute specifies the key used for the MAC; decryptionKey indicates the key used in the Triple DES encryption. By default, these attributes are set to the value “AutoGenerate,IsolateApp,” which uniquely autogenerates the keys for each Web application on the server. This setting works well for a single Web server environment, but if you have a Web farm, it’s vital that all Web servers use the same keys for MAC and/or encryption and decryption. In this case you’ll need to manually enter a shared key among the servers in the Web farm. For more information on this process, and the <machineKey> element in general, refer to the <machineKey> technical documentation and Susan Warren’s article Taking a Bite Out of ASP.NET ViewState.

The ViewStateUserKey Property

Microsoft® ASP.NET version 1.1 added an additional Page class property—ViewStateUserKey. This property, if used, must be assigned a string value in the initialization stage of the page life cycle (in the Page_Init event handler). The point of the property is to assign some user-specific key to the view state, such as a username. The ViewStateUserKey, if provided, is used as a salt to the hash during the MAC.

What the ViewStateUserKey property protects against is the case where a nefarious user visits a page, gathers the view state, and then entices a user to visit the same page, passing in their view state (see Figure 10). For more information on this property and its application, refer to Building Secure ASP.NET Pages and Controls.

Figure 10. Protecting against attacks using ViewStateUserKey

Conclusion

In this article we examined the ASP.NET view state, studying not only its purpose, but also its functionality. To best understand how view state works, it is important to have a firm grasp on the ASP.NET page life cycle, which includes stages for loading and saving the view state. In our discussions on the page life cycle, we saw that certain stages—such as loading postback data and raising postback events—were not in any way related to view state.

While view state enables state to be effortlessly persisted across postbacks, it comes at a cost, and that cost is page bloat. Since the view state data is persisted to a hidden form field, view state can easily add tens of kilobytes of data to a Web page, thereby increasing both the download and upload times for Web pages. To cut back on the page weight imposed by view state, you can selectively instruct various Web controls not to record their view state by setting the EnableViewState property to False. In fact, view state can be turned off for an entire page by setting the EnableViewState property to false in the @Page directive. In addition to turning off view state at the page-level or control-level, you can also specify an alternate backing store for view state, such as the Web server’s file system.

This article wrapped up with a look at security concerns with view state. By default, the view state performs a MAC to ensure that the view state hasn’t been tampered with between postbacks. ASP.NET 1.1 provides the ViewStateUserKey property to add an additional level of security. The view state’s data can be encrypted using the Triple DES encryption algorithm, as well.

Happy Programming!

Tags: View State